Note: A first version of this text appeared as an article in the Revue de l’Energie in 2020 in its issue n°651 (July/August 2020), under the title: “Le changement climatique à l’épreuve de la négociation! An unprecedented global governance under construction”

All of the world’s countries meet annually at the famous “Conferences of the Parties” or COPs (those linked to the Climate Convention) to agree on the objectives and resources mobilized in the fight against climate change. How were these negotiations built, how did we arrive at these different agreements on climate such as the Kyoto Protocol or the Paris Agreements and what do they imply?

____

The issue of the climate change (sometimes also called “climate disorder”) has taken on unprecedented importance in the international political and public debate over the last three decades, since the agreement of the Rio Conference on Development and the Environment in June 1992, during which the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was adopted and signed. In order to fight against climate change, three major agreements were adopted at the international level and deserve to be mentioned: the UNFCCC adopted in 1992 in Rio, then the Kyoto Protocol adopted in 1997 at the third Conference of the Parties (COP3) in Japan, and finally the Paris Agreement adopted in France in 2015, at the COP21. These agreements have the value of international treaties because they involve the majority of the states on our planet. Today, the texts on which international action will be based are the first and the last, as the Kyoto Protocol no longer has any operational provisions decided after 2020. These treaties embody the international community’s response to the progressively compelling evidence – gathered and repeatedly confirmed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – that the climate is changing and that this change is largely due to human activities. While the UNFCCC includes provisions for reporting on atmospheric emissions, i.e. emissions of direct (CO2, CH4, N2O, HFCs, PFCs, SF6) and indirect (NOx, CO, Non-methane volatile organic compounds, SO2), the Kyoto Protocol specified quantified and legally binding commitments, assigned mainly to developed countries, while the Paris Agreement can be considered as inclusive as it commits all those who have ratified it to date.

In this article, we propose to revisit the content of the main stages of this negotiation in order to appreciate its results and to shed light on the arrival point of the Paris Agreement, which also becomes a starting point for the “coordinated” implementation of actions to fight climate change at a global scale. We will begin by recalling how this subject became an object of negotiation on the way to the first Earth Summit in 1992. Then we will briefly describe the history of the first post-Rio negotiations that led to the Kyoto Protocol in 1997. The instruction of the modalities of implementation of the latter lasted eight years, but from 2005 onwards a debate was also opened on what should be done after the “first Kyoto commitment period (2008/2012)”. It will be impossible for this article to retrace the slow intellectual process that led the negotiators, little by little, to bring the issue back into the orbit of the Climate Convention (the principle of voluntary action is the only one compatible today with the principle of national sovereignty over the sectoral actions to be taken, which cannot be formulated so easily in a global manner as was possible for the Montreal Protocol for the eradication of chlorinated compounds that attack the ozone in the upper atmosphere). This pathway highlighted in particular through the crisis of the Copenhagen Conference, at the end of 2009, which against all odds saved the process in the end. We will explain why the Copenhagen Conference was not a failure, contrary to what is often said. We will then summarize the path that led to the Paris Agreement adopted in 2015. The latter constitutes the legal vault of the legislative outcome of this long process, which many will find too slow but which was necessary to make its future implementation more solid and to try to respond to the urgency increasingly exhibited by scientists under the aegis of the IPCC and by civil society, as well as by the business world, which now wishes to have some visibility on what should be changed in the future with regard to its new investments. After summarizing the legal content of the Paris Agreement, which is essential to understand the essence of this process, we will summarize the steps that marked the finalization of the RuleBook associated with the Paris Agreement and we will conclude by outlining the main advances of the COP 26 held in November 2021 in Glasgow. The objective of this article is to provide the reader with a summary of the main legal elements corresponding to the major stages of the negotiations from 1990 (the date of the beginning of the negotiations that led to the adoption of the Climate Convention in 1992 after more than a dozen sessions of the INC (International Negotiating Committee)) until 2022.

1. The Framework Convention on Climate Change

It would be too long for this article to go into the genesis of this first international treaty dealing with the fight against climate change. The origin of the awareness is distant (J. Fourier (1822), Svante Arhenius (1896) in particular, for what concerns the scientific fundamentals). For decades, there was no collective awareness of the problem, but climate science made a lot of progress. In 1979, the first World Climate Conference was held, organized by the WMO (World Meteorological Organization), followed in 1985 by a more discreet and sometimes forgotten conference: the Villach Conference, jointly organized by the UNEP (United Nations Environment Program) and the WMO. These two events were decisive in setting up the IPCC in 1988, decided at a G7 meeting in Toronto. Finally, the Hague Conference in 1989 and the Second World Climate Congress in 1990 completed the setting and contributed to an awareness of the issues related to this new problem. It was thus decided that at the Earth Summit in Rio, a first treaty would be adopted to initiate a global fight against the increase in greenhouse gas emissions (GHG). In the run-up to the Earth Summit, the first IPCC report was published, which represented the first international consensus among scientists on the issue of climate change. This consensus expressed the findings of science on the observed warming, on the increase in concentrations of GHG in the atmosphere and if fossil emissions generated by human activity were suspected to be the main cause; concerning this last issue, one could only remain at the level of presumptions. Nevertheless, this work served as the basis for the first international policy decision.

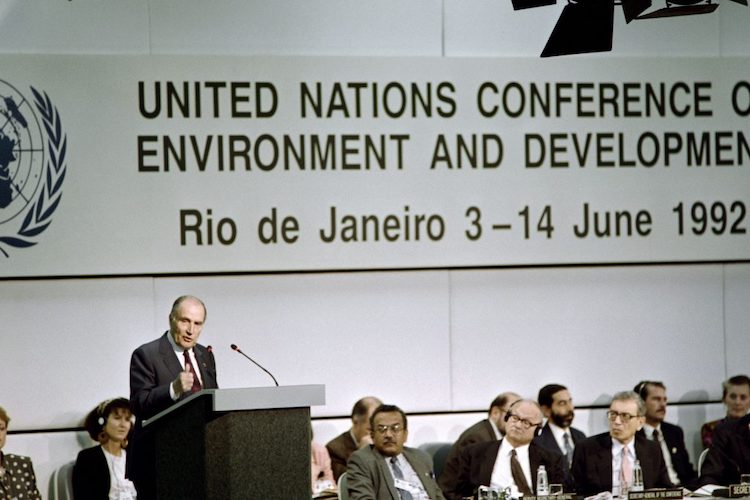

In 1992, at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro (Figure 1), the United Nations (UN) adopted a framework for action to combat global warming: the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The latter stipulates in its Article 2:

“The ultimate objective of this Convention and any related legal instruments that the Conference of the Parties may adopt is to achieve, in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Convention, stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system. This level should be achieved within a time frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner.”

Figure 1. The Earth Summit in Rio in 1992. [Source : © Moustique – https://www.moustique.be/images_gallery/sommet-de-la-terre-1992]

This Convention thus recognized that the assumptions of scientists were enough to build a treaty based on three main ideas. First, by recognizing that scientific uncertainties do not justify deferring action, the “precautionary principle” is implicitly applied. Although GHG emissions have an equivalent impact on climate change, whatever their origin, it is recognized that the most industrialized countries have today (at the time of the adoption of the text) a greater responsibility for the current concentration of GHGs. The “principle of common and differentiated responsibility” had just been constructed. Finally, by recognizing the “right to economic development”, it was acknowledged that actions to fight climate change must not have a negative impact on the essential needs of developing countries, namely sustainable economic growth and poverty eradication.

This text went beyond the simple issue of climate change to constitute a real treaty calling for sustainable development, a subject that was the topic of a parallel agreement through the adoption of Agenda 21 and the creation of the Commission on Sustainable Development at the same time as the UNFCCC, i.e. at the same Earth Summit in 1992!

The Convention was quickly signed by 196 Parties (195 States and the European Union as a regional group) and then ratified, allowing it to enter into force. These Parties have been meeting since 1992 at annual meetings of the treaty’s monitoring body – the Conference of the Parties (or COP) – to discuss what could be done to limit the increase in average global temperature resulting from climate change, and to review progress in the fight against climate change (the COP is the supreme body of the UNFCCC, i.e. its highest decision-making authority; it is complemented by two bodies, the Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI) and the Subsidiary Body for Science and Technological Advice (SBSTA), which deal with the various issues related to the implementation of the Convention and provide scientific and technological support.) In the following, we will use the abbreviation “COP”, to call (usually with an associated number) such an important meeting.

It is important to remember that even if the commitments in Rio were not quantified and if a “dangerous” level (that of Article 2) of atmospheric GHG concentration was still impossible to define, the text of this treaty was a real revolution, foreshadowing what the Paris Agreement would later become, for the collective management of a common good, in this case, the climate of the planet Earth.

However, a qualitative separation was decided with regard to the legal obligations assigned to the signatory Parties in the name of the principle of common but differentiated responsibility. The Annex I countries (the developed countries, especially the OECD countries) were more constrained than the emerging countries, the developing countries and the poorest countries. This had important consequences for the rest of the process and was one of the reasons for the weak mobilization of some countries.

2. What happened after Rio?

After the Rio Conference, several events will take place. The Secretariat of the Convention will prepare the holding of the first Conference of the Parties whose date had been scheduled in Rio. This took place (COP1) in April 1995 in Berlin. The Parties recognized that the measures decided for Annex 1 of the UNFCCC [1], when the Convention on Climate Change was signed in Rio (1992), were inadequate to stabilize GHG concentrations in the long term and that the corresponding commitment would not be fulfilled. Moreover, even though the second IPCC report had not yet been officially adopted, it was known that progress had been made in the scientific establishment of the attribution of climate change to the responsibility of human activities (the work of the Max Planck Institute in Hamburg [2] had for the first time compared the climate signal with its “natural variability” and the result, even if shy, have reality to the presumption of the first IPCC report). Despite the opposition of the USA to the future adoption of binding numerical targets (a proposal that was put forward by Europe), the creation of a negotiating group was decided by the COP (AGBM: Ad hoc Group for the Berlin Mandate) with the mandate to prepare a protocol for reducing emissions beyond 2000, together with policies and measures for the Annex 1 countries of the Convention, to be adopted in Kyoto at the end of 1997. The technical work to prepare this protocol began in mid-1995 with the establishment of the AGBM sessions.

At the end of 1995, the IPCC submitted the conclusions of its second scientific assessment report, stating in particular that “the balance of evidence suggests that there is a discernible human influence on climate”. Since then, the IPCC has not denied this assertion; it has even reinforced it in the course of its various synthesis, of which there are now six, with the sixth assessment report being finally adopted in 2022.

3. The Kyoto Protocol

The preparation of the Kyoto Protocol was the subject of intense negotiations within the UNFCCC, with strong pressure from developing countries against developed countries and conflicts over the solutions to be promoted, particularly between the United States and Europe. The United States, which had finally come around to the idea of quantified targets (although it knew that the Senate would never accept a treaty in which developed countries alone would be committed), would have preferred policies and measures to be adopted. Europe wanted policies and measures to be adopted as well, but “Common and Coordinated”, which the United States totally refused. The major breakthrough came at COP2 in Geneva in the summer of 1996, when the United States declared that it supported the quantified objectives proposed by Europe, but only if an international carbon emissions trading market be set up. Europe, like all the other countries, was taken by surprise and it was on this basis that work began on the preparations for COP 3, which was to take place in Kyoto the following year.

The important event of the year 1997 was the third Conference of the Parties which took place in Kyoto from December 1 to 11, 1997. The Kyoto Protocol was adopted: it stipulated that the countries in Annex B of the Protocol (38 of the most developed countries, a sub-set of Annex I to the UNFCCC) commit to reducing their GHG emissions by at least 5% from 1990 levels (a basket of six gases: CO2, CH4, N2O, HFCs, PFCs, SF6 and, since 2013, NF3) by 2008-2012. Articles 6, 12 and 17 of the Protocol introduced the possibility of using various flexibility mechanisms such as joint implementation within Annex 1, the clean development mechanism with developing countries, and emissions trading within Annex 1. However, the rules, modalities and guidelines for these various mechanisms had to be the subject of specific instructions from the Convention’s bodies, which took nearly four years to finalize. This was also the case for the provisions to be made in the event of non-compliance with the agreement by a Party.

The Marrakech Conference (i.e., COP7) took place in late 2001, four years after the adoption of the Protocol. The so-called Marrakech Accord, a text of about 250 pages, described the technical details of the implementation of the Kyoto Protocol’s provisions:

– the consequences of non-compliance with the Kyoto reduction targets by the Parties,

– the practical details of the market mechanisms described by the Kyoto Protocol that are emissions trading in developed countries and credit creation through Joint Implementation and the Clean Development Mechanism,

– the inclusion of “carbon sinks” in national inventories.

This international agreement was important for several reasons. First, it concluded a round of negotiations that began just after the adoption of the Kyoto Protocol, by defining its practical aspects. It provided a clear legal framework for the Parties to ratify it if they so wished, thus paving the way for its possible entry into action. Finally, it gave a clear signal on the possibility of using market-based instruments, an issue that deserves to be explored in a separate article.

The text adopted in Kyoto in 1997 at COP3 (Figure 2) and its annexes decided in Marrakech, thus constituted a corpus considered as an additional protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The Kyoto Protocol entered into force on February 16, 2005, following its ratification by Russia, which made it possible to reach the quorum of 55 States representing 55% of Annex B emissions in 1990, a condition required in the Protocol.

Figure 2. COP3 in Kyoto in 1997. [Source : © Wired – https://www.wired.com/2009/12/1211kyoto-climate-accord/]

In 2012, the overall targets for the first period of the Protocol were met despite the withdrawal of Canada and the absence of the United States, which never ratified the Protocol. Participating countries reduced their emissions by 24% from the base year, usually 1990. However, without the United States and after Canada’s withdrawal, the first period of the Protocol was binding on only 36 countries, representing only 24% of 2010 emissions, while global emissions increased by 30%, due in part to the growth of developing countries. The Kyoto Protocol, not committing the main emitting countries, was therefore not sufficient to stabilize GHG concentrations. A second commitment period, from January 2013 to December 2020, was nevertheless decided at COP 18 in Doha (2012), but its scope was even more limited than that of the first period, since some signatory countries announced that they would not be able to meet their targets (Canada, which legally withdrew from the Protocol, and Japan in particular).

The flexibility mechanisms played a certain role; in particular the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) was innovative as a vector of cooperation with developing countries. In these countries, it facilitated the financing of virtuous projects directly by companies in Annex B countries, without impacting public budgets. Despite its limitations, the beneficiary countries found it of great interest. The limits were the need for developing countries to set up rigorous carbon accounting and propose adequate projects (China was able to do this very quickly) and for Annex B countries to impose a carbon constraint on their industry (the EU succeeded in doing this with the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS)). The difficulties in renewing this mechanism in a different legal framework partly explain the tough negotiations on Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, which will be discussed below.

4. From the Montreal COP in 2005 to the Paris COP in 2015, 10 years of negotiations!

After 2005, the date of the Montreal COP11 which “consecrated” all the application texts of the Kyoto Protocol, the future had to be considered. Should we continue the logic of the Protocol at the risk of seeing several other Parties leave the process? Or should we start an other method? After two years during which the Dialogue [3] proposed by the Canadian presidency was organized, the Bali roadmap structured the discussion around four main themes at the end of 2007, decided at COP13: mitigation, adaptation, development and technology transfer, and finally financial issues.

The Parties were given a two-year deadline to reach a new international agreement. This period was undoubtedly too short to allow tensions to mature and to return to the founding principles of the Convention, which favored a voluntary approach by the Parties while respecting their sovereignty, essentially with regard to energy. The initial conditions of the Copenhagen Conference were therefore not favorable for the ultimate agreement that was sought. Nevertheless, as we will see, what happened in Copenhagen was an essential turning point for the future.

4.1. The Copenhagen Conference (COP15)

The Copenhagen Conference concluded its work on December 19, 2009 (Figure 3) after an entire night of negotiations. It was intended to consolidate the work carried out over the past two years under the Bali Action Plan adopted in December 2007, with the objective of building an architecture of long-term GHG emissions reduction commitments beyond the year 2012. At the time, the press spoke of a failure in view of the results of the COP, but what happened in Copenhagen was a major revolution for the rest of the process, a real “turnaround” in the spirit of the Climate Convention that made it possible to make the necessary shift to allow the Paris Agreement to come into existence six years later, as we will see below.

Figure 3. COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009. [Source : © IISD ENB – https://enb.iisd.org/climate/cop15/16dec.html]

In the last three days, we witnessed the confrontation between the “UN” structure and the representatives of the States themselves (119 heads of State had come to the end of this Conference of the Parties because everyone believed that a new treaty was going to be signed). There was certainly work to be done to consolidate the modalities of a collective commitment to fight effectively against climate change, through a legally binding commitment. But the meeting left with a text called the Copenhagen Accord, which the Conference of the Parties took note of, even though some countries refused to sign up to it.

It was therefore “below” a decision of the Conference of the Parties that would have considered the text to be adopted unanimously, but certainly “above” a simple ministerial declaration that would not have been mentioned in the final text of the conclusions of the 15th session of the Conference of the Parties. It was also decided to give a mandate to the AWGLCA (Ad Hoc Working Group on Long-term Cooperative Action) to prepare the basis for the work to be done to break the lock-in at the 16th Session of the Conference of the Parties in 2010 in Mexico.

The text of the Copenhagen Agreement was prepared at the level of a few Heads of State after ten days of intense discussion between the Parties (the Heads of State of the major emerging countries prepared this text, joined later by the United States, but Europe was excluded from this discussion, having only to approve the final text!) who had been presented with several successive synthesis texts. These texts, prepared successively by the Danish Presidency of the Conference, Tuvalu, China, and finally the AWGLCA Chair, were not sufficiently well received to be transformed and accepted by the Heads of State. It is therefore an unprecedented procedure that was used by a few visionary countries, who understood that it was time to force fate! The text of the Paris Agreement was initially negotiated by the USA, China, India, South Africa and Brazil. It contains twelve points that are based on the squaring of the Bali Action Plan, namely: mitigation, adaptation to climate change, development and transfer of technology and finally issues related to financing, especially in developing countries.

We will not go into detail here about the Copenhagen Accord because all these points are included in the Paris Accord. However, it is in this text that the average thresholds of 2°C and 1.5°C appear for the first time as a limit to be set to contain climate change in a text to be adopted by the UNFCCC [4].

The text of the Agreement was therefore considered by the Conference of the Parties, which took note of it. Each Party was asked to subscribe to it voluntarily and if so, it would be included in the final text. Furthermore, the mandate of the AWGLCA was extended with the objective of presenting the conclusion of its work to the 16th session of the Conference of the Parties for adoption.

Six more years of work were necessary to reach COP 21 in Paris with the step of COP16 in Cancun that allowed to restore the confidence of the Parties in the process. Remarkably organized by the Mexican government, it was in fact the first COP where the industrial world was listened to and this at the initiative of the Mexican government. Although the concept of “Business Day” was not created in Cancun, the Mexican presidency of the COP gave it an importance that would later lead to the agenda of actions. This was a major turning point in the process and a real message of hope. The Copenhagen Accord, simply “noted” by the Parties, contained the seeds of the future Paris Agreement. This can be seen by comparing the points of the latter with the adopted articles of the Paris Agreement. They constituted the legal framework of the Paris Agreement, which we describe in the next chapter.

4.2.The Paris Agreement of 12 December 2015

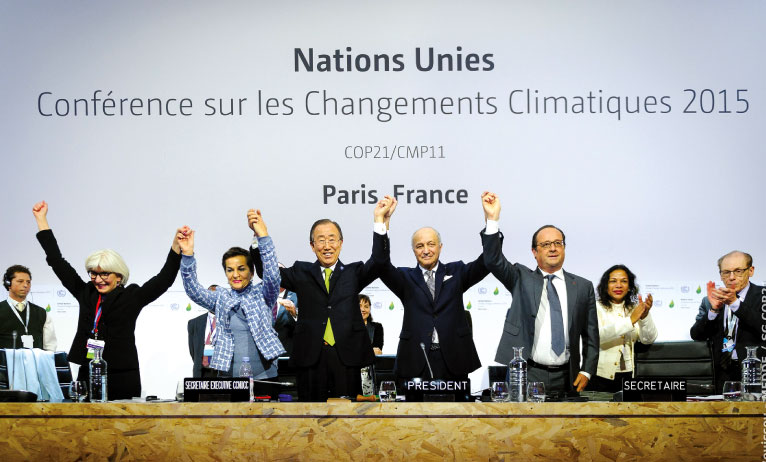

The Paris Conference ended in the early morning of December 13, 2015, after two days of intense final negotiations (Figure 4).

A historical agreement (“The Paris Agreement”) was reached and adopted in the early evening of Saturday, December 12, on the international fight against climate change. It is the result of four years of intense work and negotiations since the Durban Conference at the end of 2011. How is this agreement made up?

There is the agreement itself, which is the legally binding part under international environmental law. Finally, there is the decision that allowed the adoption of this agreement, which describes in detail the technical points that will have to be decided and put in place by 2020, to allow the effective implementation of this historic agreement. The text of the agreement is referenced as follows in the nomenclature of the Secretariat of the Climate Convention: FCCC/CP/2015/L.9/Rev.1 (Agreement) and FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.1 (Decision of the COP).

Figure 4. The COP21 in Paris in 2015. [Source : © Revue Gestion – https://www.revuegestion.ca/quel-bilan-peut-on-tirer-de-laccord-de-paris]

This text can be seen as a profound and unexpected step towards the real implementation of the Climate Change Convention. It contains all the elements to collectively build a global strategy for mitigation and adaptation to climate change as well as the roadmap to instruct the details of this strategy before 2020. In this sense, the adoption of this agreement is not the end but the beginning of a long process! We propose below to outline the main points of the agreement, in order to summarize the philosophy of a legal text of about thirty pages:

The introduction of the Paris agreement is important because it places the problematic in object of this agreement in resonance with that of sustainable development which is absolutely not contradictory with article 2 of the Climate Change Convention of 1992 as we said at the beginning of this article.

Visibility on the long-term objective

Article 2 is very clear: it covers mitigation, adaptation and resilience as well as financial aspects. The level of ambition is high:

- Containing global average temperature rise to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and continuing action to limit temperature rise to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, with the understanding that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change;

- Building capacity to adapt to the adverse effects of climate change and promoting resilience to climate change and low greenhouse gas emission development, in a manner that does not threaten food production ;

- Making financial flows consistent with a pathway to low greenhouse gas emission and climate change resilient development.

In the decision (part II. 17), the elements are made even more explicit since an indicative target of 40 gigatons of CO2 for global emissions is proposed, to help building what should be the future NDCs (NDC: “National Determined Contributions”). These objectives are extremely ambitious (not to say impossible to achieve!), but it must be understood that politically it was very difficult to stick to a reference to 2°C only, which would have meant implicitly accepting the disappearance of island states! Let us therefore remember that this article 2 sets the long-term objective that will guide the articulation of national policies in the decades to come. In short, it is a question of achieving a collective objective on the basis of autonomous decisions, NDC meaning precisely that each country sets its commitments on a purely national basis.

An unprecedented process of collective commitment

One of the original features of the Paris Agreement is that it proposes a method of commitment by the Parties that respects the sovereignty of the countries, particularly with regard to energy, while gradually and collectively building up the ambition of the commitments. The countries have to respect this process in a binding manner even if there are no sanctions as such. Thus, articles 3 and 15 make it possible to regulate this commitment mechanism. Parties committed to the Agreement are required to participate in the successive target review process (NDC) and to continue to engage in public policies related to emissions reductions (Article 3). A global synthesis process takes place every five years and will begin in 2023 with a requirement to progressively increase ambition in line with the global goal for emissions reduction (Article 15).

An investment-friendly climate regime

Several articles should be mentioned in this regard:

– article 4 describes the process of domestic commitments by countries that will gradually give visibility to investors on national strategies related to the fight against climate change,

– article 9 on financing, states that developed countries must provide financial resources to developing countries for both adaptation and mitigation. The mobilization of finance must continue until 2025 and the collective target should increase from a floor of US$100 billion per year,

– article 10 describes decisions related to technology transfer, with a desire to promote cooperative approaches to new technologies, and finally

– article 11 proposes a mechanism to help developing countries build capacity.

Transparency framework

Article 13 deals with the transparency context for implementing this agreement collectively (and also points 85 to 99 of the decision). The aim is to eventually converge the existing reporting systems between developed and developing countries, those that exist under the Convention, so that a common regime can eventually be achieved while respecting the notion of differentiation that is still prevalent in the discussions.

Carbon price and economic instruments

This topic has been the subject of many twists and turns throughout COP 21, but it is clear that the Parties have reached a very positive and unexpected outcome: Article 6 (formerly Article 3 in the draft agreement discussed upstream) deals with implementation – including through cooperative approaches (markets described by another name). After tense negotiations over the last 48 hours, everything that could be desired is present: accounting provisions, cooperative approaches and internationally transferable mitigation outcomes (through carbon markets) and a credit creation mechanism (to support GHG mitigation and sustainable development). Paragraph 5 of this article explicitly addresses the absence of double counting – a key point to ensure the confidence and credibility of the mechanism. These rules are to be adopted at the first meeting of the Parties to the Agreement, after it enters into force. Point 136 of the decision recognizes the importance of carbon pricing: “136. Also recognizes the importance of providing incentives for emission reduction activities, including tools such as domestic policies and carbon pricing”

Adaptation, resilience and loss and damage

The agreement places a strong emphasis on adaptation, resilience and the issue of loss and damage in Articles 7 and 8. On loss and damage, i.e. the physical damage caused by climate change, there was clearly a compromise. In exchange for accepting (in the decision) that there is no automatic liability or compensation, the least developed countries gained recognition of the concept of “loss and damage” in Article 8 of the agreement. However, the requirements for countries to take action or provide support to particularly climate-vulnerable countries is weaker than they might have hoped.

5. What has happened since COP 21?

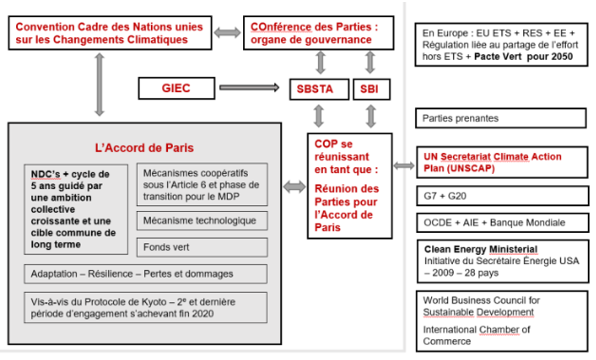

Since the adoption of the Paris Agreement, which really founded a new cooperative approach to the long-term resolution of the climate change issue (see Table 1 summarizing the bodies involved in the debate), several years have passed. They have made it possible to draw up the book of rules for implementing the articles of the Paris Agreement (COP22 in Marrakech, 23 in Bonn, 24 in Katowice and 25 in Madrid at the end of 2019). There was at least one remaining issue that had not yet been resolved, and that is the one related to the rules on Article 6, the one dealing with economic mechanisms, reminiscent of the market mechanisms of the Kyoto Protocol. From the beginning of 2020 to the end of 2021, the negotiation process was put on hold because of the health crisis and there were no physical meetings of the Parties. The UNFCCC Secretariat did, however, organize interim meetings of the UNFCCC subsidiary bodies, but the Parties did not want these meetings to be considered as negotiations. Nevertheless, they allowed a channel of exchange between the Parties to continue, which in particular allowed the agenda for the Glasgow Conference to be set correctly.

Table 1: Structure of the different bodies of the climate convention and important instances of the associated international political debate.

6. The 2021 Glasgow Conference (COP 26): towards the beginning of the implementation of the Paris Agreement?

The 26th Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC was held in Glasgow, Scotland, from Sunday, 31 October to Saturday, 13 November 2021, after a two-year hiatus due to the coronavirus pandemic. The two weeks of discussions resulted in the Glasgow Climate Compact, several high-level sectoral commitments, and a set of decisions that complement the Paris Rules by operating Article 6 of the Paris Agreement and establishing transparency requirements for Parties when reporting both their emissions and climate actions.

Figure 5. COP26 in Glasgow in 2021. [Source :Vov 5 World – https://vovworld.vn/fr-CH/actualites/climat-ouverture-de-la-cop-26-a-glasgow-1042095.vov]

Let us detail some of the decisions taken in Glasgow.

The Glasgow Climate Pact – The COP, and the two bodies linked to the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement (the CMP and the CMA[5]) approved their respective decisions, entitled “Glasgow Climate Pact” (see [9]).

These decisions call on Parties to submit enhanced NDCs in 2022, with 2030 targets aligned with the temperature targets of the Paris Agreement. The pact also calls on governments to “accelerate the development, deployment and diffusion of technologies, and the adoption of policies, to move to a low-emissions energy system,” including “accelerating efforts toward the unabated phase-down of coal-fired power and the phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies,” the first time such language has been found in a COP decision.

The text of the Glasgow Compact (GCA) emphasizes that greenhouse gas emissions have to be reduced by 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 if the world is to remain on track to achieve carbon neutrality by mid-century (paragraph 22).

Article 6 – Parties approved decisions on the three elements of Article 6: Article 6.2 (“cooperative approaches that involve the use of internationally transferred mitigation outcomes for nationally determined contributions”); Article 6.4 (“a mechanism to contribute to the mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions and support sustainable development”); and Article 6.8 (“non-market-based approaches”). The Glasgow COP thus set the end of long years of discussion to establish the practical modalities for implementing the Article 6 imagined at COP 21 in Paris.

Common deadlines

Countries agreed to language that “encourages” Parties to update their NDCs every five years and that each set of updated NDCs should cover a 10-year period.

Strengthened transparency framework

The Parties have adopted rules defining how they should report their national emissions inventories.

Kyoto Protocol CDM Guidelines

It has been formally decided that the Executive Board of the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) will no longer register any new applications for registration, renewal of crediting periods or issuance of Certified Emission Reductions for emission reductions occurring after December 31, 2020. Any new applications must now be made under the mechanism of Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement.

Nationally Determined Contributions

Parties should “revise and strengthen the 2030 targets in their nationally determined contributions as necessary to align with the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement by the end of 2022, taking into account different national circumstances.”

New collective quantified target on climate finance

The COP recognized that financial contributions had not met the $100 billion per year target for 2020 and discussed ways to increase collective contributions for the next period to 2030. These discussions were inconclusive in Glasgow and will continue in 2022 in Egypt.

Losses and damages

Decisions establishing the role of the Santiago Network within the Warsaw International Mechanism on Loss and Damage were made. The Santiago Network will “catalyze” technical assistance to prevent, minimize and address loss and damage in climate-vulnerable developing countries. At this stage the decisions have not been translated into financial commitments.

7. Conclusion

The international negotiation that sought an agreement to manage the reduction of anthropogenic GHG emissions began thirty years ago! Since 1990, when the Negotiating Committee was set up and held 11 sessions before Rio, the history of the negotiations has seen three turning points (Rio, Kyoto, Copenhagen) and a conclusion materialized by the Paris Agreement. It took 25 years from Rio to Paris! We have tried to summarize above the main points of this long way, how the scientific sphere has influenced it and how this point of balance, constituted by the Paris Agreement, has gradually imposed itself. Let us note, for the French reader, that French diplomacy has played an important role since the beginning: let us simply recall that the prefiguration of the Rio Agreement was chaired by a French diplomat (Jean Ripert) who played a decisive role with some key negotiators in the establishment of the Climate Convention and that the Paris Agreement was prepared and proposed under the French presidency of the COP (Laurent Fabius and Laurence Tubiana). Even if the Parties now have all the rules for the implementation of the Paris Agreement, it will take a few more years to clarify some of the details, and to see the strengthening of collective ambition in order to get closer to the objective as soon as possible. The reports of the IPCC working groups that have recently been published (the last one from Group III on the economics of climate change was published in April 2022) are unequivocal: collective action must be taken without delay if we are to be able to meet the commitments made in Paris at the end of 2015.

Of course, the Parties have not yet resolved all the economic and financial issues related to the implementation of the Paris Agreement. Many economists often advocate that there should be a carbon price in the global economy to signal where to invest [6]. This is surely an interesting and theoretically correct mathematical solution that does not apply as easily in a world as diverse in terms of inequalities (see [7] and [8]). Only with the implementation of appropriate policies and measures to solidify all the institutional frameworks that make them attractive to investment can we envisage large-scale cooperation that may help to establish more inclusive price signals, for example through the use of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

However, it can be noted that many decisions have been taken so far and that this international law is increasingly used by many stakeholders to justify this or that decentralized decision going in the right direction (industry, finance, civil society, etc.). This is the first time in the history of humanity that such a situation will occur, i.e. managing a “common good” such as climate through an international agreement without encroaching on the prerogatives of national sovereignty. Given the speed with which science has confirmed the origin of the problem, one may be surprised that it has taken so long to reach an agreement. After all, twenty years is not much time compared to the time needed to negotiate the GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) towards the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO): almost 40 years! And the problem of climate change is much more conflictual than the issue of international trade! Indeed, the issue of GHG emissions is deeply linked to our economic development, our lifestyles and the way we produce and use energy. All activities contribute. It is therefore easy to understand why binding and collective public policies are difficult to decide. Finally, in the course of the history of this negotiation, several events have occurred that could have threatened it or even stopped it! It must be noted that this process has been resilient to shocks and difficulties up to now [7].

On the side of the actors, and in particular of the energy world, there is now a real awareness and a capacity to put it at the service of positive actions, which was not shared by all industry some twenty years ago. Let’s take advantage of this alignment of the planets to move forward! We can only hope that the governance that has taken so long to build will be implemented without delay. Thanks to this agreement, the world can only progress towards constructive international relations and the safeguarding of a common good.

Glossaire :

AGBM: Ad hoc Group for the Berlin Mandate

AWGLCA : Ad Hoc Working Group on Long-term Cooperative Action

CCNUCC : Convention Cadre des Nations Unies sur les Changements Climatiques

CMP: COP serving for the Meeting of Parties

CMA: COP serving as the meeting of Parties to the Paris Agreement

COP : conférence des parties

ETS : Emissions Trading Scheme

GATT : General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

GES : gaz à effet de serre

GIEC : Groupe d’Experts Intergouvernemental sur l’Evolution du Climat (GIEC)

MDP : Mécanisme de Développement Propre

NDC : National Determined Contribution

OMC : organisation mondiale du commerce

OMM : organisation mondiale météorologique

ONU : Organisation des Nations Unies

SBI : Subsidiary Body for Implementation

SBSTA : Subsidiary Body for Science and Technological Advice »

SEQE : Système d’échanges de quotas d’émissions

Notes & references

Cover image. [Source : https://www.fisicaquantistica.it/spiritualita/i-galattici-cosa-volete-veramente-cosa-cercate]

[1] Les pays, dits de l’Annexe 1 avait des obligations plus contraignantes que celles des pays en développement, notamment en matière de « reporting » des émissions de GES. Ils s’étaient notamment engagés de manière volontaire à réduire leurs émissions de GES en 2000 aux niveaux de 1990.

Convention sur les Changements Climatiques (CCNUCC) – 1992 –https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/CCNUCC_20100727.pdf

[2] On notera qu’en 2021, Dr. Klaus Hasselmann, un physicien allemand, a obtenu le Prix Nobel pour ses travaux (il était directeur du Max Planck Institute de Hambourg en 1995)

Le Protocole de Kyoto (CCNUCC) – 1997 – https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/kpfrench.pdf

[3] La COP décida à Montréal de lancer le “Dialogue pour une action concertée de long terme destinée à permettre de faire face aux changements climatiques par un renforcement de l’application de la Convention”, le lien https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2005/cop11/fre/05a01f.pdf

L’Accord de Copenhague (CCNUCC) – 2009 https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2009/cop15/fre/11a01f.pdf (pages 5 à 8)

[4] S’accorder sur un seuil de dangerosité du changement climatique tel que le mentionnait l’article 2 de la Convention Climat, n’a pas été chose aisée. Dans les premières années de synthèse du GIEC, on exprimait des seuils en concentration atmosphérique de GES. Après de longs débats, l’objectif de ne pas dépasser les 2°C d’ici la fin du siècle fit l’objet d’un consensus parmi les experts du GIEC. Ainsi, ce qui avait été au départ un objectif politique (proposé dans un texte européen avant la réunion de Kyoto !) non traduit à l’époque dans les textes internationaux, le devint peu à peu suite aux différentes analyses des scientifiques qui considérèrent que cet objectif pouvait être considéré comme un seuil au-delà duquel les perturbations des écosystèmes sensibles pourraient s’accélérer. Cette limite de 2°C a été reprise par la CCNUCC, et retenue comme le cadre pour orienter les actions de réduction des risques du changement climatique et la définition des politiques climat. Dans ce cadre, l’objectif de 2°C a été retenu dans l’accord de Copenhague, adopté à la COP 15 (2009), puis confirmé par les accords de Cancún, adoptés à la COP 16. On retrouvera ce seuil naturellement dans le texte de l’Accord de Paris.

L’Accord de Paris et la décision de la COP – 2015 https://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/convention/application/pdf/french_paris_agreement.pdf et https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/docs/2015/cop21/fre/10a01f.pdf

[5] CMP: “COP serving for the Meeting of Parties” liée au Protocole de Kyoto

Les rapports du GIEC (5 rapports de synthèse WGI, WGII, WGIII) – https://www.ipcc.ch/

CMA: “COP serving as the meeting of Parties to the Paris Agreement” liée à l’Accord de Paris

[6] L’AIE (Agence Internationale de l’Energie), indiquait il y a une dizaine d’années dans un de ses rapports, que 70% des réductions qu’il fallait faire, pourraient être effectuées avec des technologies existantes ! A-t-on donc réellement posé la question des conditions de rentabilité de ces dites technologies partout dans le monde, sans même parler de toutes les technologies qui alimentent plus les débats théoriques que de réelles expérimentations de nature industrielle (capture et séquestration du carbone, réutilisation du carbone, émissions négatives, etc..) ?

[6] Caneill J.Y., 2020 – Le changement Climatique à l’épreuve de la négociation ! Une gouvernance mondiale inédite en construction, La Revue de l’Energie, n°651 / juillet-août 2020

[7] En 2001, les États-Unis s’étaient retirés du processus lié à l’accord de Kyoto ; ils avaient de nouveau intégré le dialogue international fin 2007 à Bali. Plus récemment, les États-Unis se sont retirés de l’accord de Paris en 2017, pour le réintégrer en 2021 !

Finon D., 2019. Carbon policy in developing countries: Giving priority to non-price

Instruments. Energy Policy 132 (2019) p. 38–43. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301421519302927

Finon D., Les politiques climat-énergie dans les pays en développement : priorité aux instruments hors prix du carbone, L’Encyclopédie de l’Energie, Mars 2021

https://www.encyclopedie-energie.org/politiques-climat-energie-pays-developpement-carbone/

Le Pacte de Glasgow – Décisions des trois organes CMA, CMP et COP (en anglais) :

https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cma3_auv_2_cover%20decision.pdf

https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cmp16_auv_2c_cover%20decision.pdf

https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cop26_auv_2f_cover_decision.pdf